The game industry’s largest convention,  the E3 Expo just took place. Reportedly, one of the highlights of the show was a demo of a new game called Adrift on the Oculus Rift platform. Adrift simulates a reality in which the gamer finds himself floating above the Earth alone on a decaying space station seeking out oxygen and a way to escape. Apparently, after experiencing a virtual reality game like this, returning to the first-person shooter format is a total buzzkill. Adam Orth, the creative lead of Adrift, said Oculus’ VR platform allows him to create a deeply emotional gaming experience never before possible.

the E3 Expo just took place. Reportedly, one of the highlights of the show was a demo of a new game called Adrift on the Oculus Rift platform. Adrift simulates a reality in which the gamer finds himself floating above the Earth alone on a decaying space station seeking out oxygen and a way to escape. Apparently, after experiencing a virtual reality game like this, returning to the first-person shooter format is a total buzzkill. Adam Orth, the creative lead of Adrift, said Oculus’ VR platform allows him to create a deeply emotional gaming experience never before possible.

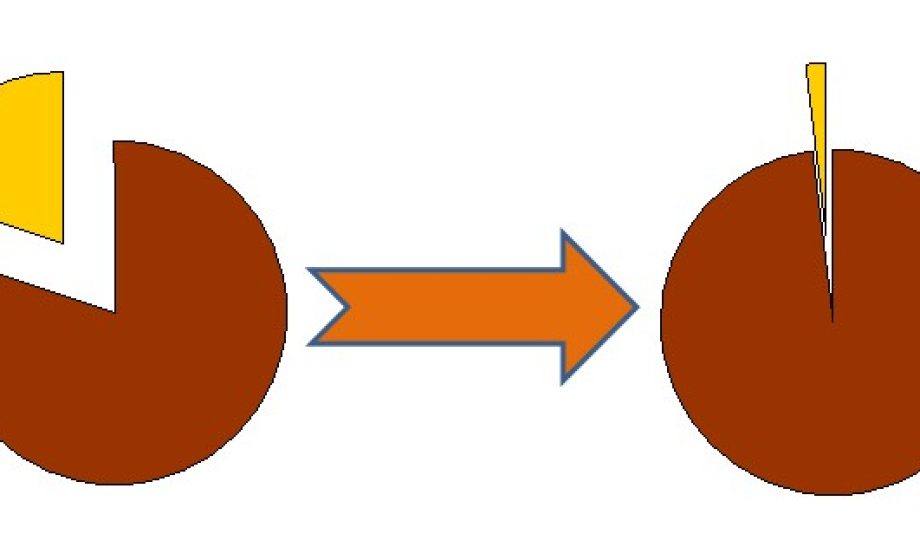

When Facebook announced its acquisition of Oculus VR three months ago for $2 billion, my mind began racing in several directions. The first reflexes were typical, along the lines of, “Do I have any portfolio companies to sell to Facebook?” or “Should I be paying more attention to virtual reality startups for some quick exits?” But after a few days, I started thinking about the wider implications of this acquisition, specifically that:

In acquiring Oculus VR, Facebook may have locked up an option on a whole new domain of innovation

A lot of analysts debated the merits of Facebook Oculus VR purchase, especially as it came on the heels of the widely-heralded $19 billion WhatsApp acquisition. Perhaps virtual reality will fulfill the promise of its evangelists and one day make $2B look like a bargain, or perhaps, as some analysts said, Facebook simply has too much cash on its hands. Time will tell.

However for me, a broader implication of this transaction is that Facebook took a potential IPO-candidate out of the game early, and thus deprived the rest of us from riding the virtual reality wave, if we believed in it, by investing in Oculus VR.

In a brilliant piece in the Rude Baguette a few months ago, Appsfire Co-founder Yann Lechelle explains persuasively how the App Stores are anti-long tail. For reasons of their quasi-monopoly on distribution, the inclination to promote in-house apps, the non-requisite of having several apps in the same vertical, the influence of featuring, App Stores tend to accelerate the Pareto Principle and encourage a rich-get-richer dynamic where only a small percentage of Apps generate any significant revenues. As Chris Dixon recently pointed out, “popular apps get home screen placement, get used more, get ranked higher in app stores, make more money, can pay more for distribution, etc.”

In so many sectors, we are moving toward a winner-take-all dynamic

Let’s take another example, high-frequency trading. As Michael Lewis explained in his delightfully readable bestseller, Flash Boys, Wall Street banks, with their immense amounts of financial and computing resources are able to leverage their resource advantage to detect nano-second trading variations and generate enormous profits to the detriment of outsiders.

Here in France, the Banque Publique d’Investissement, BPIFrance financed 95% of French venture-backed startups in the second half of last year. This comprised its direct investments in companies as well as its indirect fund-of-funds activity.

In the U.S., the angle is even more acute. As Frank Bruni referencing Thomas Piketty recently opined, “Over all, the United States’ economy outperformed France’s between 1975 and 2006. But 99% of the French population actually enjoyed more gains in that period than 99% of the American population. Exclude the top 1%, and the average French citizen did better than the average American.” Combined with the U.S. electoral map, the phenomenon has led to a polarization of party primaries, encouraging candidates to lean toward the extremes in order to attract the funders.

My concern about the trend toward a winner-take-all dynamic is that it enables defense of the status quo over disruptive innovations.